From Ghetto to Grand Boulevards: The Transformation of Prague’s Jewish Quarter

Prague’s Jewish Quarter—known historically as Josefov, the Jewish Ghetto, and the Fifth Quarter—is today one of the city’s most elegant districts. Its wide boulevards, Art Nouveau buildings, and luxury boutiques offer little hint of the dense, impoverished, and deeply segregated community that once existed here. The transformation of this space from medieval ghetto to prestigious neighborhood is one of Prague’s most dramatic urban evolutions.

This article explores how Josefov changed over centuries, culminating in a radical redevelopment at the end of the 19th century that erased most of the original quarter.

Life Inside the Ghetto: Boundaries and Restrictions

For centuries, Prague’s Jewish population lived in an enclosed district, surrounded by walls and gates that were physically locked at night. Until 1783, Jewish residents could not legally live outside the ghetto. Even when permitted to leave temporarily, they were required to wear identifying symbols so they could be distinguished from Christians.

After Emperor Joseph II issued reforms granting Jews more freedoms, wealthier families began moving into nearby areas of Old Town. Although the legal border disappeared, its symbolic weight lingered; residents of the time even recalled a rope stretched across the street to mark the cultural divide.

Survivors of the Past: Pinkas Synagogue, Maisel Synagogue, and the Old Jewish Cemetery

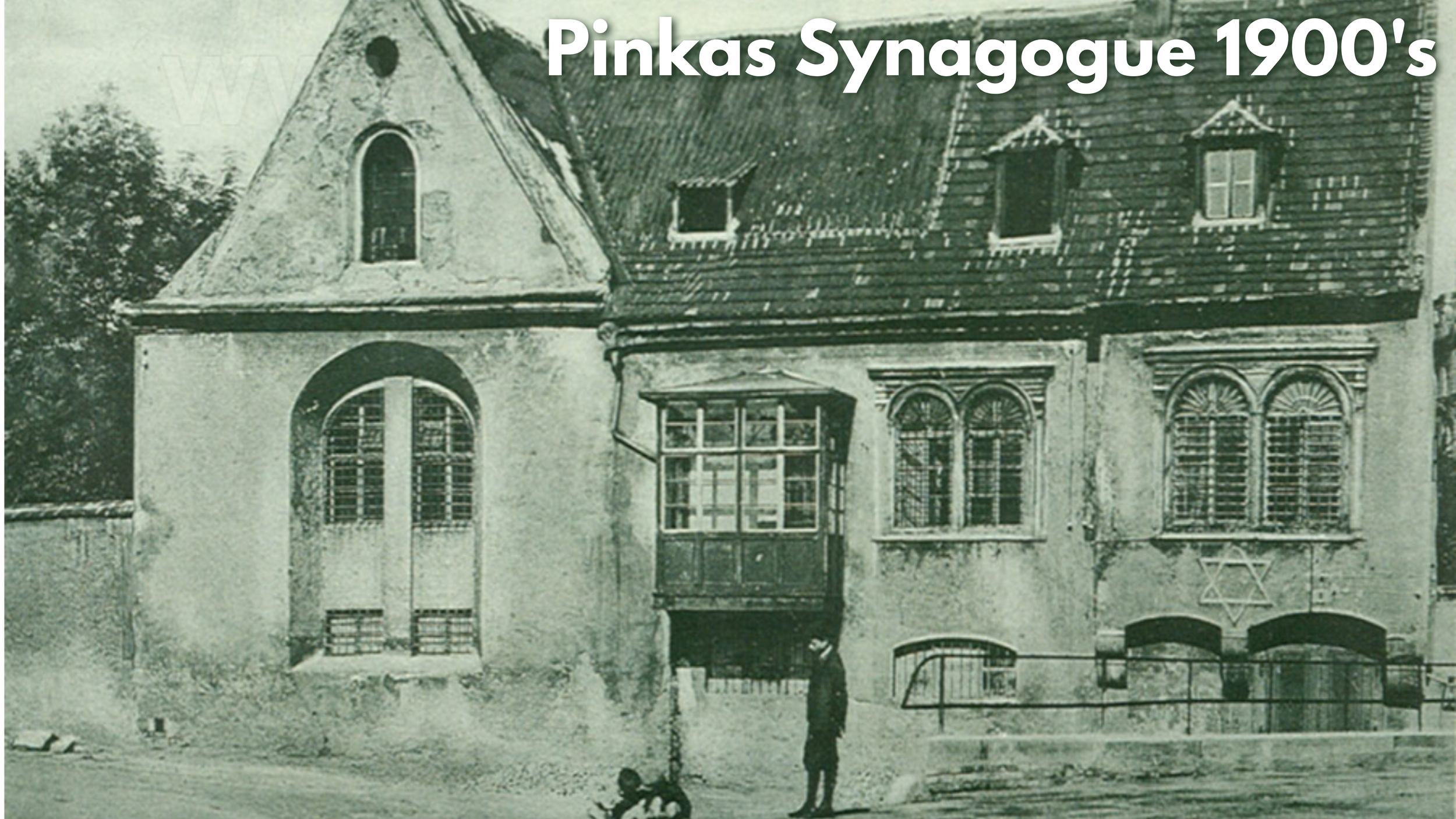

Among the few major structures to survive the redevelopment are the Pinkas Synagogue and the Old Jewish Cemetery.

The Pinkas Synagogue, the second oldest in Prague, now serves as a memorial to Holocaust victims, its interior covered with the names of Czech Jews murdered during World War II.

The Old Jewish Cemetery, used for nearly 300 years, remains an iconic symbol of the Jewish presence in Prague.

The Maisel Synagogue, financed by renowned Jewish Quarter citizen Mordechai Maisel, is now a museum of Jewish heritage and history.

A Neighborhood Declines: Poverty, Overcrowding, and Changing Demographics

In the decades following 1783, the population of the ghetto changed significantly. While wealthier Jewish families moved out, poorer Christians moved in.

In 1843, roughly 6,200 people lived in the ghetto, about 5,900 of whom were Jewish.

By 1880, only 45% of residents were Jewish.

Conditions deteriorated rapidly. The area lacked clean water and sewage systems, leading to frequent outbreaks of diseases such as typhus. Overcrowding and poverty turned the quarter into one of the least desirable places to live in Prague.

Some streets gained a notorious reputation. Široká Street, for example, became lined with brothels. One of the most famous was owned by private detective Leopold Friedmann, who reportedly used the workers as informants. Old photographs show houses draped in white cloth—an informal signal that a brothel operated inside.

The Great Transformation: Sanitization (Asanace) of the Jewish Quarter

By the late 19th century, Prague officials concluded that the only solution to the area’s severe public health and infrastructure problems was complete redevelopment. This process, known as sanitization, paralleled similar projects in Paris, Vienna, and other European cities.

The plan, officially approved in 1896 under the motto Finiš ghetto (“End the Ghetto”), encompassed more than 365,000 m² of land, including both Josefov and parts of Old Town. The project required:

The demolition of nearly 620 buildings

The displacement of approximately 7,000 residents

The expropriation of properties often owned by multiple families (sometimes up to 40 owners per structure)

Compensation was notoriously low. One resident bitterly remarked that selling his house under these terms felt like selling “a coat for the price of a button.” Nevertheless, sanitization moved ahead, altering the district’s layout completely. One of the biggest sanitation developers was Vácslav Havel, the grandfather of the first Czech president, Václav Havel.

Paris Street: A Boulevard Born From Redevelopment

One of the first results of the sanitization project was Pařížská (Paris) Street, conceived as a wide, elegant boulevard meant to “air out” the cramped slum. Although the idea that fresh air would cure disease was simplistic, the street became a central feature of the new district.

Originally intended to extend all the way to Wenceslas Square, the plan was scaled back to avoid demolishing even more of Old Town. Today, Paris Street is among Prague’s most prestigious addresses, lined with luxury boutiques and upscale residences owned by billionaires, politicians, and celebrities.

Lost Landmarks: The Bassevi House and Other Demolished Sites

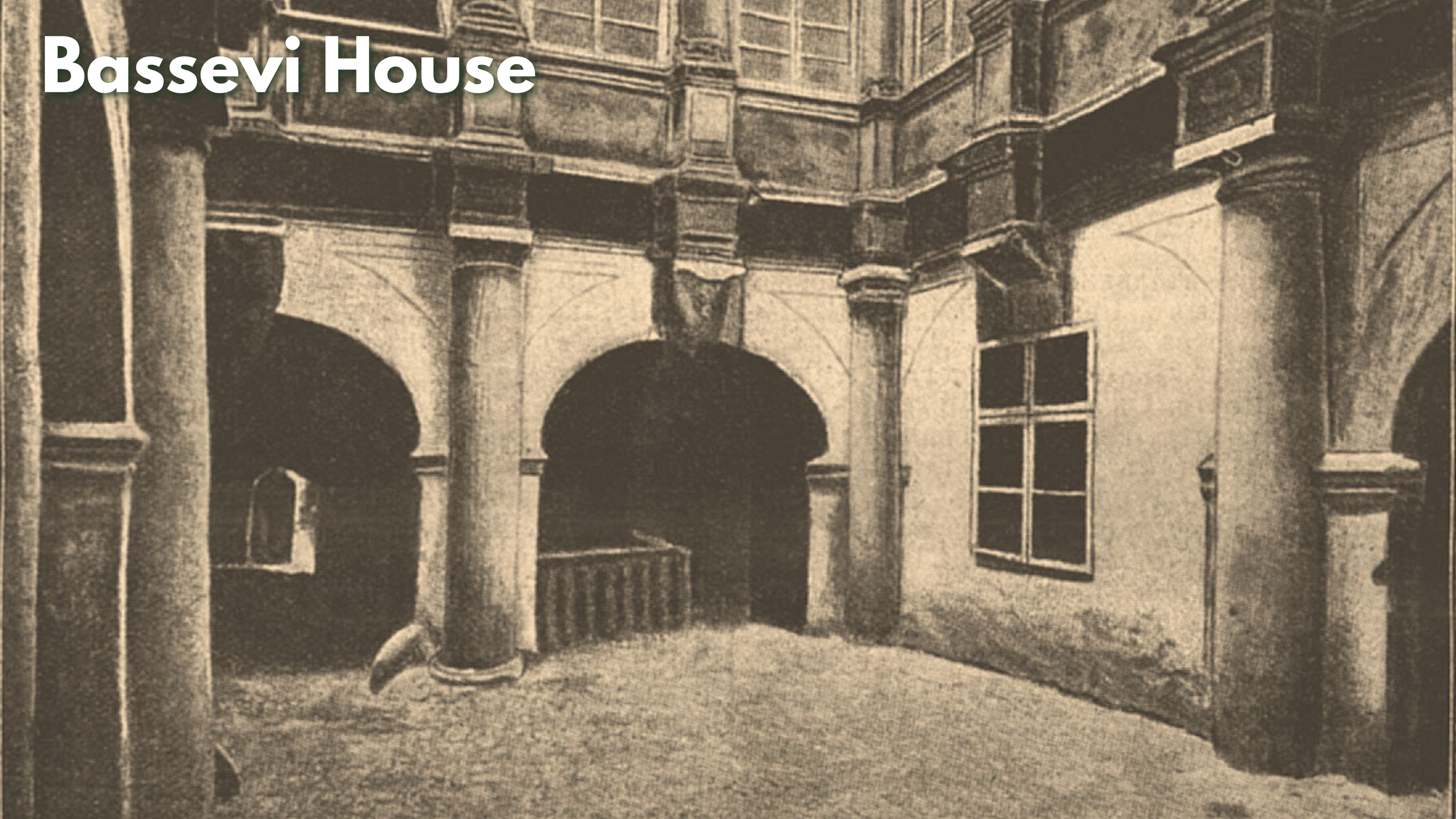

Among the most significant buildings lost during redevelopment was the Bassevi House, home of Jakob Bassevi of Verona, a prominent Jewish banker and adviser to multiple emperors, including Rudolf II. Unusually for the time, Bassevi was granted the right to live outside the ghetto and was one of the first Jewish men in Prague to receive an aristocratic title.

His house was demolished and replaced with a modernist building by Otakar Novotný, now used as office and co-working space.

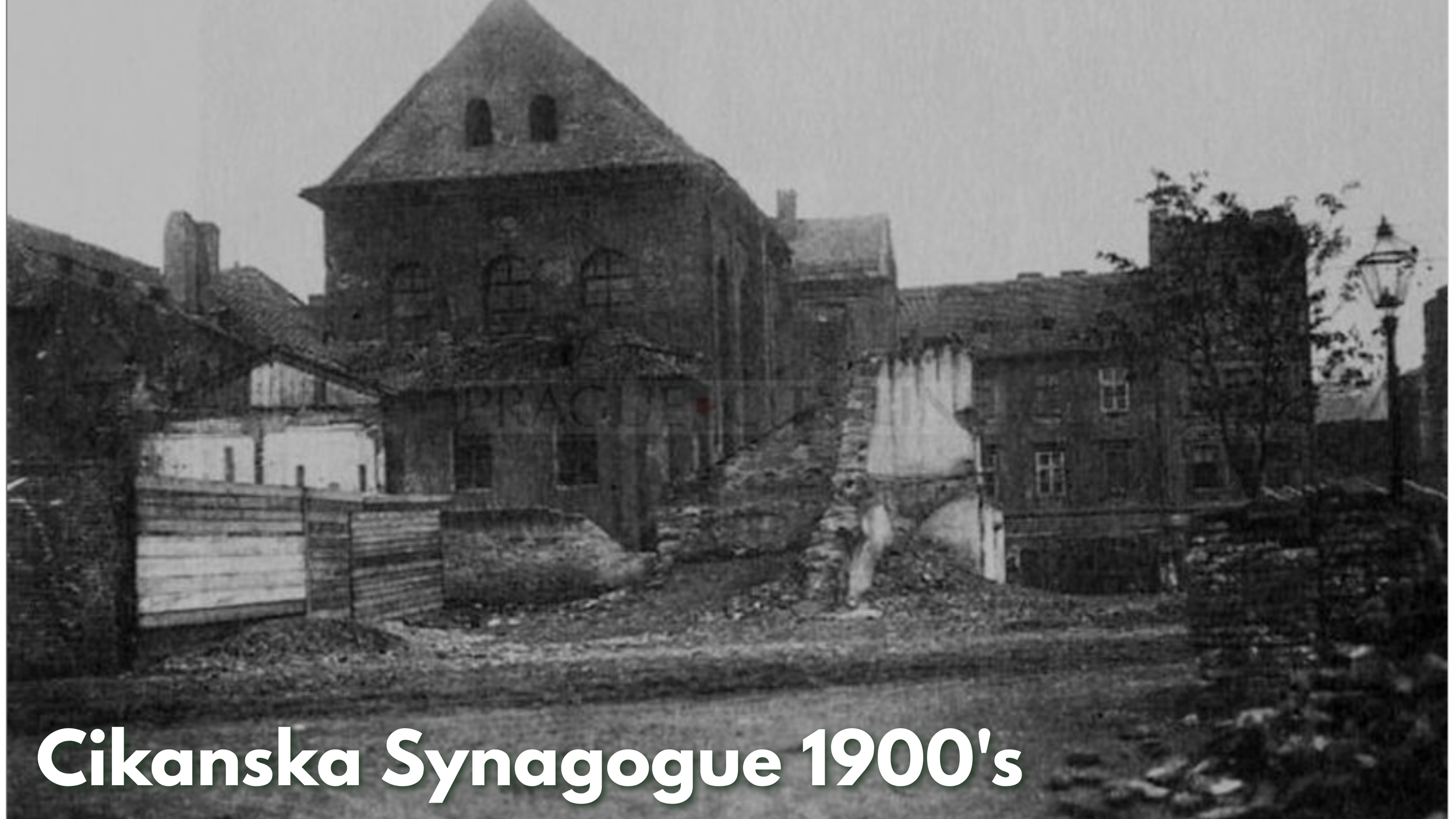

Nearby, two synagogues—Bassevi’s own synagogue (Velkodvorská) and the Cikanská Synagogue (where Franz Kafka is believed to have had his bar mitzvah)—were also torn down.

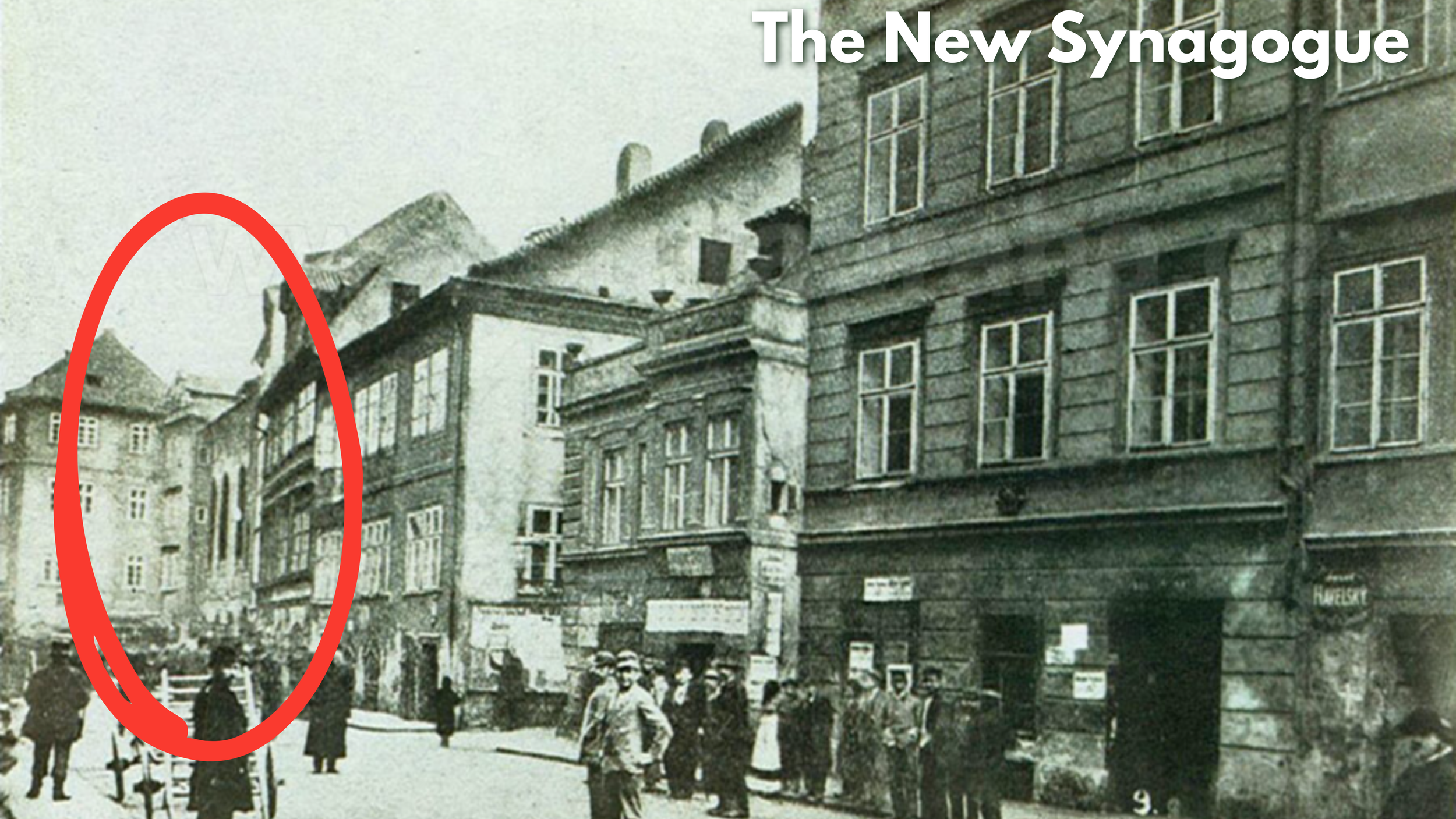

Nearby once stood the New Synagogue, founded in the late 16th century. Despite surviving fires in 1689 and 1754, it was ultimately demolished during the district’s redevelopment.

Language, Identity, and the Push Toward Czech Culture

Before its redevelopment, the primary language spoken in the Jewish Quarter was German. German dominated home life, business, and publishing. Even Kafka, although bilingual, wrote his literary works in German.

One of the leading figures behind the redevelopment, Dr. August Stein, advocated for the “Czechification” of Prague’s Jewish community. He later co-founded the Prague Jewish Museum in 1906—an institution that today administers the synagogues and the Old Jewish Cemetery.

Preserving What Remained: The Old-New Synagogue

The Old-New Synagogue, dating to 1270, is the oldest still-functioning synagogue in Europe and one of Prague’s most important historical monuments. It survived both centuries of ghetto life and the sweeping demolition of the sanitization period.

Old photographs show houses tightly pressed around it, including a once-famous late-night tavern known simply as “Den,” which was legendary for its after-midnight crowds. The police shut it down even before redevelopment began.

Today the synagogue stands in a spacious square—an unintended monument to the dramatic transformation of the neighborhood.

A District Reinvented

Sanitization undeniably improved public health and infrastructure, and brought architectural beauty to the area. But it also erased a vast amount of cultural and historical heritage. Only fragments of the original ghetto survive: its synagogues, cemetery, and a handful of remaining buildings.

The modern Jewish Quarter is both a rebirth and a reminder—an elegant district built atop centuries of struggle, resilience, and cultural richness.

WRITTEN BY VALERY

Licensed Prague guide and co-creator of Real Prague Guides (50K+ YouTube subscribers). My company, 100 Spires City Tours, leads some of the highest-rated tours in Prague.

📷 Instagram: @realpragueguides

📺 YouTube: Real Prague Guides

🎫 Book a tour: tours-prague.eu